In 2007 I set myself up for a fall.

I thought I had the beginnings of a great idea – but to test it properly meant I’d need to be willing to risk public embarrassment and failure.

That is how I found myself lining up with a really nice – but also really intimidating – bunch of guys on the banks of the River Wharfe. Guys that had “done this sort of thing before”. Some Guys with 15 international Caps for England or even the England team manager at the time (now sadly passed away).

Now, looking back through my photo folders, I’m really grateful to my controller (score-keeper) on the day, Robert Brown, for taking these photos during the competition for my own memorabilia.

I was drawn to fish the afternoon session (which meant that the river would have already been fished hard by the competitors in the morning). This would give the perfect challenge for my ideas…

The one thing I had on my side was that, whatever the result, I knew I would learn something valuable. It would be just as useful to get put well and truly in my place rather than to have a false, unjustified faith in a mere theory.

And my Big Idea?…

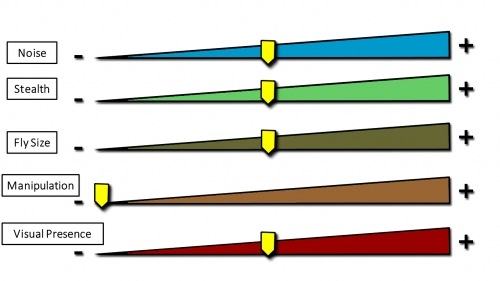

That you could use a simple judgement of the amount of “background noise” in and around the river to decide how large your fly should be (relative to the naturals), how much (and what kind) of stealth you would need, how drab/colourful your fly needed to be.

In other words you could choose whether to “whisper” or to “shout” depending on how much competing “noise” you were up against.

I also strongly suspected that sticking to “close copy” (to the human eye) fly patterns was a huge mistake.

Now, I am not for one moment going to pretend that my thinking on those factors was anything more than fairly crudely developed at that time. I also hadn’t had the pleasure, honour and benefit of the intensive study of some of the best exponents of fishing with simple, suggestive (but highly functional) flies in the shape of elite Japanese “tenkara” anglers.

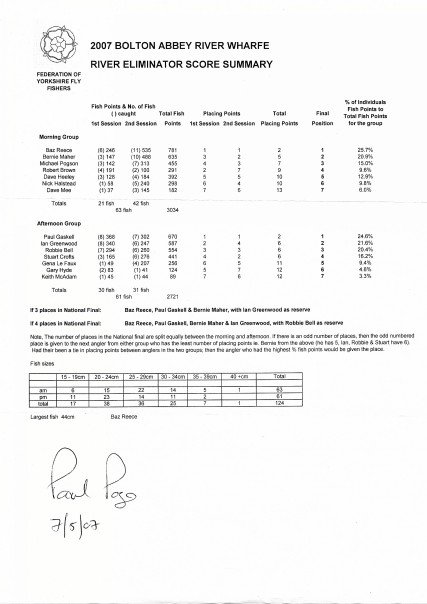

To cut a long story short, I somehow managed to win that competition – and the fishing I experienced during the contest was actually very much like my usual non-competitive trips. So that way, I knew I had something worthwhile to develop.

I recently came across my score sheet for that day, which is a nice memory – even if I have now left that competitive experiment behind (now it has served its “calibration” purpose for me). But I need to say that all of the folks that I met during my little experiment were extremely generous and supportive. Thanks guys for making it a really enjoyable experience – and yeah, something I’m proud of.

So, fast forward eight years and I found myself writing my very first e-book based on the (by now extensively developed and tested) idea which lets you massively simplify your choices on stream. And with that simplification, you get to raise your success and give yourself a lot more space to enjoy the experience. Winner, winner – chicken dinner.

That is how come I ended up being able to boil down so many of the most complex combinations of decisions you make on-stream into five main elements.

After spending time getting used to wearing this idea, I found that the easiest way to imagine it was as a small bank of “slider” controls (like the ones you get on a music studio mixing desk or on a stereo “graphic equalizer)). The further to the right that you move any slider control – the stronger that feature will be in your fishing.

The neat thing about the sliders is that when you move one, it lets you balance things out my moving others in response. With only five “sliders”, the possible combinations of each are pretty much infinite; but the choices are made fairly easy by using the top one (the amount of background “noise”) to guide what you do with all the other factors.

The example for how I built (and then tested) the fly-size selection cheat sheet is shown by taking the conditions you find on stream and judging how “noisy” the river is. This is basically how much turbulence, colour and flow the river is carrying. That lets you imagine where the “noise” slider would be on the scale. Then, you simply move the fly-size slider to match it. The cool thing about that is you can apply it either to making your artificial fly smaller or bigger than the natural insects on the water – or even smaller or larger than the “usual” sizes for particular artificial patterns.

So, that is one (pretty simple) way to represent my big idea…and the surprisingly cool thing about all that is:

It works

Paul

So, What do you think? Let me know in the comments below…

I like your theory, Iv’e always gone by if the usual stuff isn’t working try something unusual. A fall day on the river saw heavy leaf litter in the water, this tends to stain the water and make fishing difficult. After an hour of nothing I sized up to a number 10 stiff hackle in vibrant purple and started catching fish, not a stellar day but much improved. I’ll test out your theory again tomorrow and see what happens. Thanks for sharing your knowledge , it’s much appreciated.