What possible benefit to you – a modern fly fisher – could come from knowing about Japan’s historic professional “survival” fly fishers known as known as the Shokuryoshi (or 職漁師 in Japanese)??

It turns out there’s a stack of benefits – but only if you’re not too stuck in your thinking (and there are even surprising lessons for western competition anglers too I believe).

I’d even go as far to say that it’s almost impossible to feel and acquire the fundamental character and tactics of tenkara if you don’t get some sense of the Shokuryōshi and related mountain culture. It was the razor thin edge between survival and death within their way of life which brought the importance of fishing knowledge, skills, efficiency and the deep connection with the natural world into sharp focus. Of course, you may not be interested in tenkara, but there is still much you can learn from Shokuryōshi.

One way to get to a useful answer is to ask a different question:

“Why did these expert “professional” anglers (who provided fish for Japanese mountain village communities) choose fly fishing as their main method?” (why not bait or netting?)

But before I try to answer that question, it’s important to understand a bit more background info for these truly awesome, highly skilled mountain-men (historically it was a male profession).

Why the funny name?

The word “Shokunin” refers to an artisan/master craftsman and “ryōshi” is a fisherman – so the “mash-up” of the two words creates Shoku-ryōshi “Master Angler” (Note: The “ō” gives a long “o” sound like in “crow” rather than the short “o” in “hot” but that character doesn’t always work in webpage addresses etc. So, even though it’s not correct, I’ll use both spellings in this article). They are the true, original tenkara anglers:

This mastery was held in high regard – and their skillset revered alongside the spiritually and culturally important mountain hunters of the “Matagi” tradition. In fact, a person described as a Matagi or a Shokuryoshi would often be one in the same person. It’s just that their responsibilities would shift depending on the time of year. While Matagi hunt in winter, Shokuryoshi generally fish in spring through to fall/autumn.

You can find out much more about the Matagi and their rich culture on this link – but it’s enough to know that the skills and culture found in these hardy survivalists share a huge amount of common ground. So for a lot of what follows, there will be A LOT of transferable skills and culture between the two groups.

Shokuryoshi skills

Growing up in the mountains ingrains physical skills – such as the ability to walk smoothly and efficiently over wet rocks and rough river-valley terrain – along with an encyclopaedic knowledge of edible plants and fungi. As well as other essential knowledge – such as mountain navigation in all seasons, rock-climbing, gathering wild edibles and the skills to make clothing and kit by hand – a deep understanding of fish behaviour could mean the difference between a community surviving the winter – or not.

That last point is not to be taken lightly…

The Tragedy at O-Akiyama

John and I were shown the graves of an entire village of eight families close to Yamada-san’s home in Akiyamago. That village (named O-Akiyama or “Great Autumn Mountain”) was probably founded by people who had been defeated in battle and fled to the mountains to try to make a life there. It was one of (or possibly THE) oldest settlement(s) of the area. Because the terrain is so steep, it is impossible to create rice paddies, so crops like millet and buckwheat had to be grown instead.

In 1783, their crops had failed and, cut off from nearby settlements by the deep winter snows, every single member of the eight households starved to death – despite desperately eating tree bark and doing anything they could to survive. Without their crops, they did not have enough knowledge of local plants, roots or other wild edibles to forage or capture enough food ahead of or during the snow (which frequently falls to a depth between 5 and 8 metres – or 16 to 26 ft – deep in Akiyamago).

For a reality check: People in villages such as this would need to eat nymphs collected from the riverbed stones as well as grasshoppers and any other available protein as a normal part of what it took to survive.

Knowing this, it highlights how important the white spotted char (the “iwana”) was to mountain life.

This particular salmonid fish (Salvelinus leucomaenis) is able to colonise further upstream into high mountain reaches of river systems than other Japanese “trout” species. Where they have colonised, the ready supply of high quality (and delicious) protein combined with the calcium available by eating the crisped-up bones meant they were absolutely central to the survival of mountain settlements. They can be smoked, salted and dried above fires to be preserved over the winter (and then also used as the base for savoury stock) as well as eaten fresh.

Both the fish and the people skilled in capturing them would understandably be regarded with deep respect.

While showing us around the memorials to each member of the eight families who perished, Yamada san told us how “heavy” and sad the place always made him feel. He thinks that the hard-won knowledge of people familiar with Shokuryoshi and Matagi skillsets would probably have saved this group of eight families.

It makes him sad to think that having fled from defeat in battle (and so being unfamiliar with mountain life of that region) they would have lacked the specific survival skills passed down through generations of mountain-folk.

It was easy to see how much regret Yamada san had for these people who died through a lack of knowledge that even today he (as a professional Shokuryoshi and Matagi) could have passed on to them…

The take-home message is that, when the margins between life and death are so thin – it is a deep knowledge of the local environment and all that lives in it that created and secured a future for mountain settlements in Japan.

Being willing to pay attention to all the inter-connected aspects of the natural world – and especially having a deep knowledge of the fish that was so central to mountain life – was (and always will be) the key to being a successful fly fisher. That is true whether your life depends on it or not – although any recreational angler should take the opinions and methods of “survival” fly fishers very seriously indeed.

Aside from any discussions about effectiveness, it is important to have respect and reverence for the people who lived and died to develop and pass down these methods and approaches.

The Difficulty in Separating Strands of Mountain-Culture

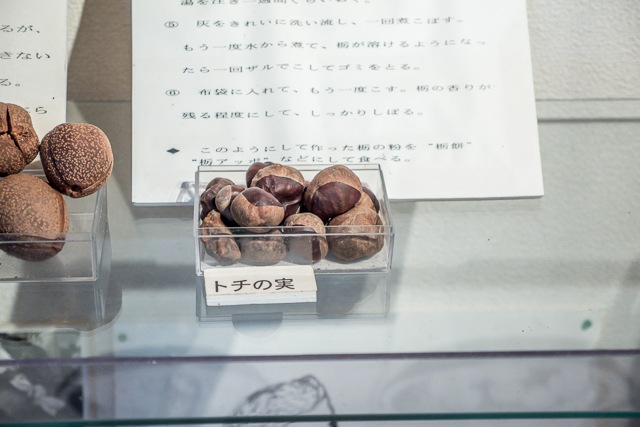

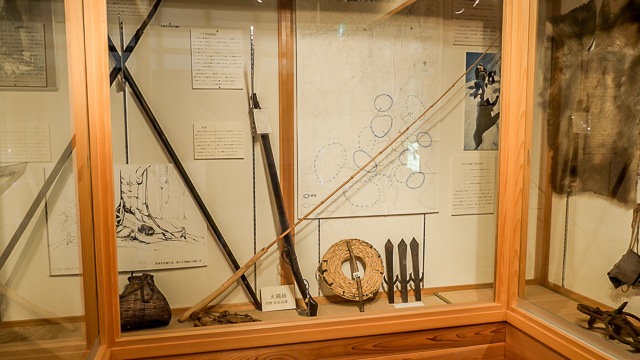

In the excellent local museum and visitors’ centre in Akiyamago, you can get real insight into the tools and skills needed to survive in the mountains. It is notable that the Shokuryoshi “tools” of bamboo fishing rod, horse-hair fly line and woven creel are NOT displayed separately from the tools of mountain hunters of the Matagi tradition. Instead it seems to be a separation by season rather than being activities that were undertaken by separate groups of individuals – which makes it natural to display their equipment and information together as a single exhibit.

So what about those tools?

Rods of the Shokuryoshi

The long bamboo rods used by Shokuryoshi were designed for landing fish immediately – without fuss. Normally somewhere around 10 to 13 feet long (3 to 4 m), they would be considered stiff in comparison to many modern recreational tenkara rods. However, they were still flexible enough to be “loaded” by horsehair tenkara lines and create a fly-casting “loop”. We are not talking about a total “pool cue” or “broomstick” action here!

Since they were tools for professionals (and not works of art), they were made quickly by harvesting and then straightening simply by heating over a fire and then bending/shaping around a shokuryoshi’s knee before dunking in cold water to help set the shape.

Their length and their strength did, however, make them heavy – given the number of casts – and especially drifts – (with high rod-tip position) performed while fishing simple wet fly patterns in fast-flowing rivers and streams. Enter the long handle…

For a number of practical reasons, long tung-wood handles were often favoured for many shokuryoshi rods. Tung wood is relatively light (not a million miles from balsa in terms of grain/texture) – but when fashioned into a long handle would provide a degree of counter-balance to the long bamboo “blank”. They were also a source of leverage when braced against the arm – allowing the reach to be extended without becoming too fatiguing.

Before casting physics gurus cry out that this makes no difference to overall swing-weight, I have two things to say…Firstly, the effort required to create rotation during the “translation” phase of casting is definitely influenced by where the weight is distributed (in relation to the pivot point around your grip). Secondly, the time spent drifting a fly is massively greater than the time spent completing a pick up and lay-down cast…so an excessively nose-heavy rod becomes more of a pain to fish with. Casting takes less than a second, drifts are around 5 seconds…

The other feature of separate tung wood handles (for example those favoured by Shigeo Yamada of Akiyamago), would be that they could be drilled to accept the bamboo rod blank. This meant that, by choosing bamboo stems of a consistent diameter for the “butt” section of each rod, it was easy to replace broken rods.

This made the handle much more valuable and, in fact, Shigeo Yamada would store multiple spare rods around his fishing grounds – only carrying his tung-wood handle to and from those fishing areas (since the handles took much longer to make). If he ever broke a rod, he simply found his nearest stashed bamboo stem rod and slid it into the ready-drilled handle recess.

In more recent years rods made from fibreglass and then graphite – came into use and both Yamada san of Akiyamago and Hirata-san of Shiro-Tori use graphite rods made by Gamakatsu. The very obvious feature of those rods is that they are still powerful and quite stiff compared to the modern preferences of ultra light-line recreational (often catch and release) tenkara anglers.

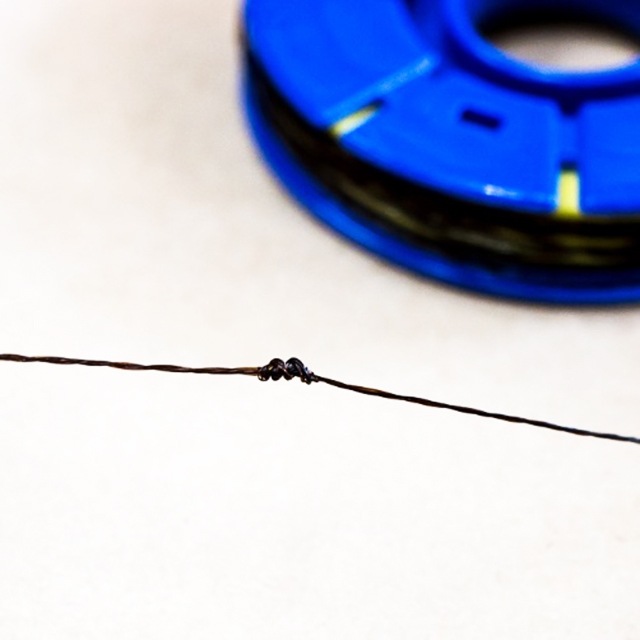

Shokuryoshi Lines and Tippets

A significant feature of anglers who have grown up in the Shokuryoshi tradition is their enduring attachment to hand-furled horse-hair lines. Again, both Yamada-san and Hirata-san use modern graphite rods BUT still prefer horsehair over modern alternatives.

Yamada-san’s horsehair lines for Akiyamago are quite long as the river is wider and more powerful than most Westerners imagine when they think of “mountain streams”. Yamada san fishes his powerful graphite rods up to 4.5m long and usually level (un-tapered) horsehair casting lines of 6-metres, plus around a metre of tippet.

Hirata-san of Shiro-Tori in Gifu prefecture (also descended from a Shokuryōshi tradition) favours stiff, long rods (often Gamakatsu again!) and both tapered and sometimes level lines made from furled horsehair. His lines are typically in the 4 to 4.5m range (sometimes with finer, furled nylon tip sections) plus around 1.2 metres of tippet. You can learn more about Hirata-san in his in depth online Masterclass course here.

Originally (before the invention and availability of nylon tippet material), the Shokuryoshi would use silkworm-gut silk. Small hanks of that silk would be soaked in vinegar in order to allow strands to drawn out and then furled together to make a tippet line.

This material would be expensive and was also (like horsehair) brittle if not periodically wetted. Is it reaching to far to guess that, in the absence of available silk tippet, a Shokuryoshi would opt for horsehair as a tippet material? I have heard this mentioned in conversation, but I can’t lay my hands on explicit proof of horsehair as a tenkara tippet material at this moment in time. Watch this space for developments.

Shokuryoshi Flies (Kebari)

While there appears to be multiple different patterns of fly (kebari) used within particular regions, it does seem to be true that families would pass down their preferred dressings from father to son. Of course, these would morph over time as each angler put their own personal touch to those dressings. A really interesting photographic study from the early 2000s shows quite a wide variety of local lineages of patterns in the Akiyamago region. Those family lines of dressing styles were pretty distinctive and they also sometimes seemed to reflect immigration/new settlement (where patterns were brought in from other regions or areas).

Overall, one of the most common feature of Shokuryoshi kebari seems to be the use of stiff-barbed hackle feathers from roosters to create simple wet fly patterns. Simple, no-nonsense impressionistic “buzzy” fly patterns. Of course, softer feathers appear in particular patterns and some are slim, winged rather than hackled patterns too – and that is a fascinating study in its own right.

Shokuryoshi Creels (kawabachi)

Woven and/or made from tree bark, these creels would be lined with fresh bamboo leaves. Fish would then be layered alternately so that they were individually wrapped in bamboo leaves to keep them protected. Shigeo Yamada would store those creels full of fish behind waterfalls where they would be kept naturally cool until he had filled enough creels to carry them back down to Akiyamago.

The Importance of Observing Nature as a Shokuryoshi

Winter Protein & Winter Green Vegetables: Enter the Mountain Hare

For a strong reference point on mountain life, it is worth watching the 1958 version of the film “The Ballad of Narayama” which highlights the constant obsessions over two things: Food and Death in Japanese mountain villages. The film centres around the customary practice of when a person reaches 70 years of age, they would be taken to the top of the mountain to “meet their god” (i.e. freeze to death).

While this film is obviously painfully close to the situation of the families that died in O-Akiyama, you might well wonder what this has got to do with mountain hares. Well in addition to the obvious protein source, mountain hares were also used as an ingenious and (perhaps to modern urban society) quite distasteful method of obtaining essential vitamins.

Basically, the hares (whose fur turns white in winter) are well adapted to finding and eating difficult to obtain green shoots in the winter and spring. So, because plant material is quite slow to digest, killing a hare in winter means that its digestive tract would often be packed with those nutritious green shoots.

Tying off the gut from throat to rectum created a strange kind of “vegetarian” sausage (though clearly not suitable for actual vegetarians). These were packed with nutrients and would also save you from spending the calories it would take to forage those shoots for yourself.

“Biohacking” Mountain Hare Hunting

Over the course of a good winter, you might be able to shoot 100 rabbits or hares. However, someone who was lucky/well-off enough to be skilled in falconry could catch maybe 300. Since falconry was out of the question for most Shokuryoshi and Matagi of humble villages they – again – used their powerful observation abilities. They noticed, for instance, that the hares responded to different predators (including hunters) in different ways.

When hares are pursued, they often run, then retrace their tracks and leap sideways a large distance before tearing round in a chaotic manner to throw predators off their trail. That, coupled with their speed and agility, makes them difficult to catch or shoot.

BUT – when they hear the sound of the wings of a bird of prey cutting through the air (particularly the “Tonbi” kites that you see so often around Japanese mountain river valleys) – their automatic defense is to freeze absolutely motionless. It turns out that his reflexive reaction can be hotwired…

Warada

Exploiting that “freeze” response to the sound of a hawk, hunter/fisher folk of Japanese mountains created sound-making (and possibly shadow-casting) decoys called “warada”. These were disks woven from straw – sometimes including a wooden throwing handle.

When skimmed towards a hare, the sound of the dense, slightly rough straw-weaving cutting through the air would cause that hare (or rabbit) to freeze. That made them much easier to catch or shoot. It is even said that, sometimes, the reflex is so strong that it is possible to simply walk up to the hare and pick it up.

Isn’t that an amazingly clever, yet simple, tactic to exploit the natural tendencies of hunted quarry? For me it is a perfect example of “biohacking” an evolved response.

Avoiding Over-exploitation

This deep connection with nature also extended to the important understanding of not over-exploiting natural populations and resources. Whether it was leaving enough fungi and plants to recolonise after foraging (Matagi and Shokuryoshi never harvested an entire patch) or whether it was the sustainable hunting of populations of game animals (particularly including black bear, “serow”, mountain hare, pheasant and iwana) – avoiding over-exploitation was essential. This behaviour code and philosophy is reinforced through the ceremonial offerings of gratitude to the mountain god – and in fact to all life within the mountains.

Even as recently as the 1960s and 1970s there have been cases of Shokuryoshi banding together to fight the causes and impacts of pollution from the expansion of industry. Naturally, they were the first to notice these problems through the effects on their local fish populations.

This, again, shows the close connection and natural understanding of the mountains, forests and all creatures living there. But when it comes down to their ability to catch fish “on demand” using fly fishing tackle – it is the deep understanding of the fish and the whole river valleys where they live that is the real secret to it all.

Married to that understanding of fish, their familiarity with natural materials also allowed the Shokuryoshi to recognise horse-tail fibres as the perfect ingredient for casting lines (and bamboo as a fly rod material). The horsehair lines readily form a “fly casting loop” and propel flies accurately and lightly to their target. The slight stiffness, strength when braided and density combined to create a really great tool for fly fishing.

Of course, fly fishers of all angling traditions from around the world (from Izaak Walton through Pesca alla Valsesiana to the Macedonians) also knew all about those ideal characteristics. So, whatever branch of fly fishing you try today, it started out with a horsehair line…

In the Japanese mountains, mobility and portability are crucial to survival. Knowing this, it’s easy to recognise these important reasons that the Shokuryoshi selected fly fishing as the most effective method of gathering fish (most often “iwana” but also yamame and amago at slightly lower altitudes).

Lessons for Modern River Competition Anglers

Although not a form of “survival” angling, possibly the closest (artificial) model of the conditions that shaped the tenkara practiced by Shokuryoshi could be modern competitive river fly fishing. The same combinations of efficiency, effectiveness and deep knowledge of fish and the systems that they live in are key.

Which is why I find it fascinating to note the similarity between the development of the long fly rod/hand-knotted/High rod-tip French leader systems and the mechanics at play in hand-knotted horsehair lines and long rods…

Ironically, modern recreational tenkara anglers have an unwritten (but seriously-regarded) rule to AVOID holding tenkara competitions. It is felt that competition might increase the chances of the best anglers becoming more secretive rather than sharing their successful approaches. That openness and willingness to share is a huge bonus for us as foreign tenkara anglers.

That being said, among the many things that have useful and interesting cross-overs from Shokuryoshi tradition to western competition methods (whether you use them purely for fun or for competing) is the deep appreciation of pacing and efficiency.

I’ve written before about “optimal foraging” in behavioural ecology and how that applies to competition angling. The short version of that is that when your catch rate in one specific “patch” of river drops to the average catch rate for the whole river section – you should move on to find another productive “patch”.

As well as that general consideration of how quickly and efficiently you can cover water (which is embedded into every single movement/casting technique and tackle-construction of the Shokuryoshi) – it is important to observe the character of the environment you are fishing.

Hisanobu Hirata knows to specifically tailor his pace of coverage and angles of approach depending on whether he is fishing low-fish-density catch and kill waters versus higher density (but also higher fishing pressure) catch and release waters. This is something we had reinforced by many modern top-class tenkara anglers too (including Masami Sakakibara).

Shokuryoshi Skills in Modern Recreational Tenkara

Particularly in genryu (remote headwaters) exploration branches of tenkara, the acquisition of a knowledge of edible plants and fungi is a respected component of being a tenkara angler. This is also important to many honryu (large main-rivers of mountain regions) and keiryu (accessible small and mid-size rivers) anglers too. The more remote (and longer) your expedition, the more vital it will be that you can live off the land during your trip.

When staying in guest houses in mountain villages, the meals you are served will often include LOTS of locally-foraged “sansai” (edible plants) and “kinoko” (mushrooms). Whether pickled, served as tempura, grilled or added to “nabe” stews, you will experience the very delicious flavours of the land surrounding you. Those distinctive flavours contribute a very identifiable and valuable character to the whole experience of fishing tenkara in Japanese mountains.

At the same time, understanding the importance of avoiding over-exploitation and allowing replenishment of any foraged natural resource is essential. While this is well understood for plants and fungi and by people with strong connections and lots of experience of mountain culture, the most obvious exception to that attitude is probably the widespread over-exploitation of fish populations via catch and kill fishing.

When it comes to the physical act of fishing, of course all of the skills of positioning, casting and animating your fly are grounded in skills developed by the Shokuryoshi.

Similarly. the sawanobori (river trekking/waterfall climbing) aspects of reaching fishing grounds and covering water in Japan’s mountainous river valleys obviously encourage the development of the natural movement and balance that would be hard-wired into historic Shokuryoshi. Just walking around the river environment without slipping or having to put your hands down all the time – while maintaining an easy balance and natural weight-distribution clearly comes from the same skillset.

Goto san on easy ground in a genryu setting

People like Sebata-san would be able to cover ground smoothly and deceptively quickly. I myself had to rush and work really hard to keep up with Goto-san as she confidently and easily picked her way along a section of Genryu during a brief shared fishing session. I used my hand on rocks and crouched several times where she remained upright, not using her hands for balance while stepping on the sides of wet, slippy, rounded boulders (and I have been a keen rock climber in my time).

It is all part of that strong connection to the mountain environment and the natural world – and it is exactly what is missing from so much of modern life and careers indoors under fluorescent light.

Shokuryoshi: Round up of what Modern Fly Fishers Can Learn

So, to answer the question set out right at the beginning of this article:

- The long, hard hikes and climbs between village and fishing grounds (and then the transportation of fish to be smoked, dried or simply brought back wrapped in bamboo leaves) all combined to make portability and efficiency essential.

- The time taken to gather bait is time better spent catching fish – and powerful mountain rivers full of boulders are not possible to net efficiently (plus simply carrying the nets – even without the fish – would be a super-human task).

- Flies can catch a large number of fish before needing to be replaced (unlike baited hooks), meaning – again – that the opportunities to catch fish were maximised. In fact, in Hirata-san’s hard-earned style of fishing, he has even worked out the fastest and most efficient casting stroke which also avoids tangles for the very same reason.

- The fly that is in the water catches the fish.

- The more you develop an appreciation of efficiency (including when to give up and when to persevere – and the overall pace of coverage), plus the ability to move effectively through the terrain while taking in the important details and clues – the better you will be.

But those benefits are only possible with a deep knowledge of nature, a deep knowledge of the habits of fish and their prey – plus a deep knowledge of effective fly fishing techniques. The fact that “skill” is elevated to such a high status (and cannot rely on fancy gadgetry) is what makes tenkara so interesting. The process of close, careful observation of the fish you want to catch AND the surrounding ecosystem that supports it over extended periods of time is the best foundation for your tactics.

It is also the reason that learning about it is guaranteed to improve your enjoyment and success in all branches of river fly fishing.

If you enjoyed this, please smash the share buttons like crazy (with our thanks)

Paul